In 1896, when Homer Plessy challenged the new racial caste system that forbade Blacks from sitting alongside whites on trains, the United States Supreme Court held that such "Jim Crow" laws were constitutional. By so doing, the Supreme Court ensured that within a decade, no Blacks held high elected office anywhere in the South, that Black voting became a nullity, and that Black businesses were either eliminated outright—or directly controlled by white "benefactors."

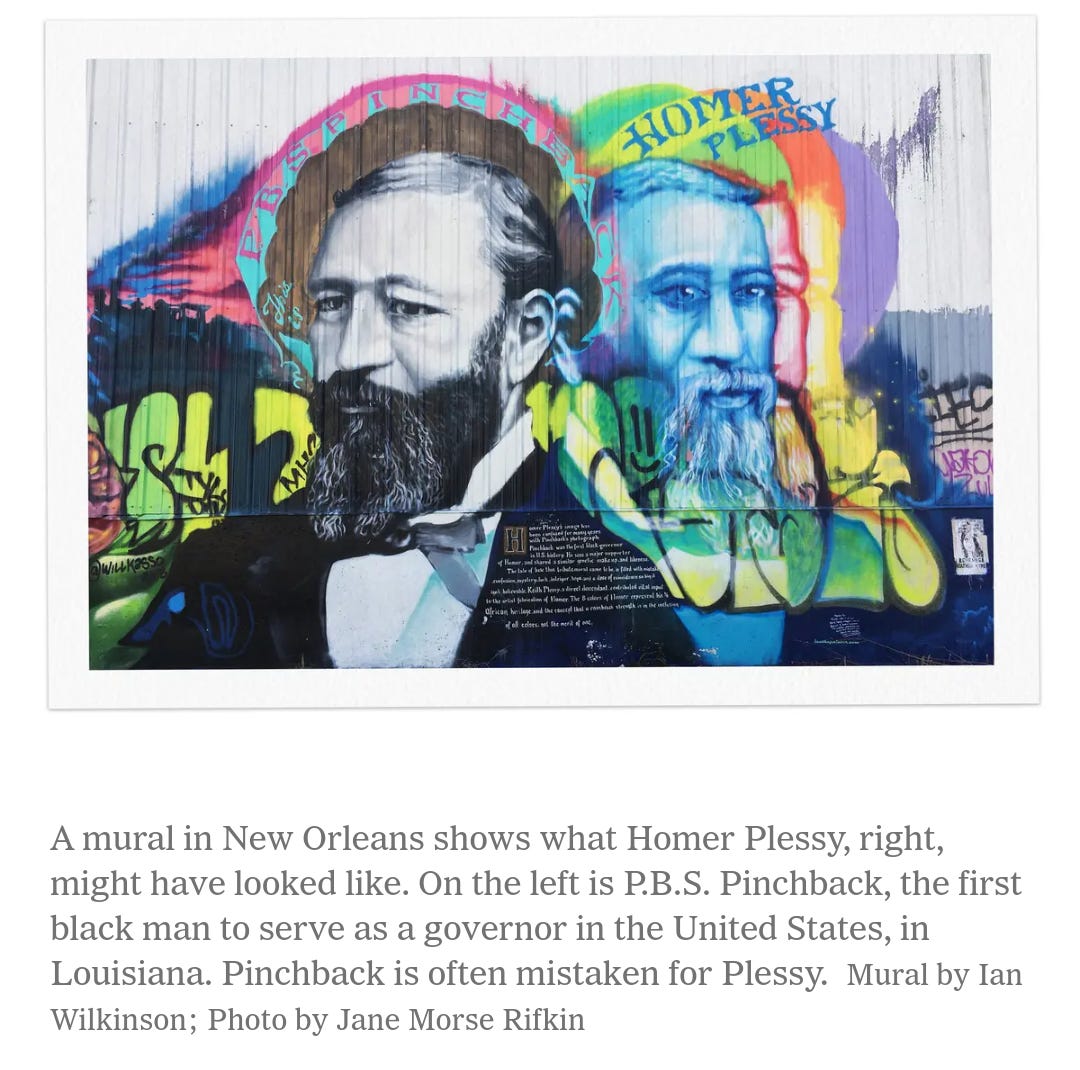

But who was the plaintiff, Mr. Plessy?

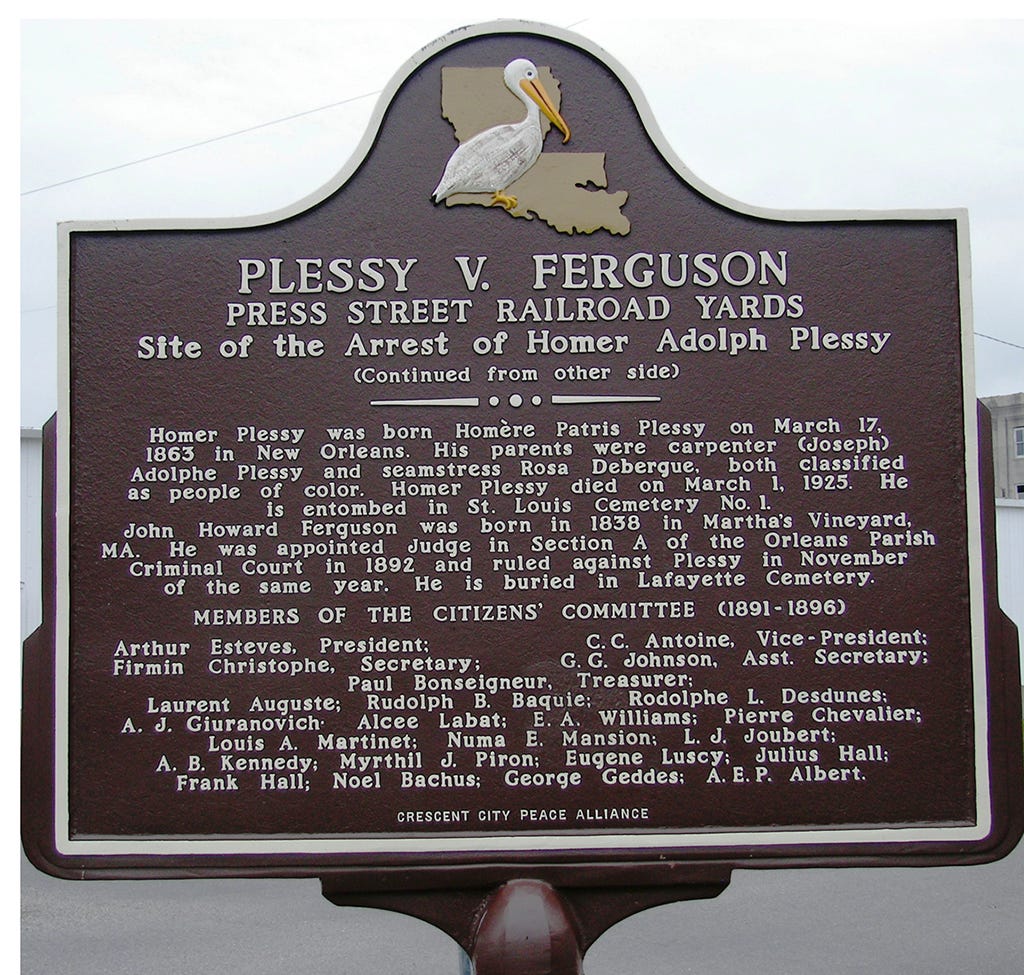

Homer Plessy was born on March 17, 1862, in New Orleans to Joseph Adolphe Plessy and Rosa Debergue, both of whom were Creole. Plessy's grandfather, Germain, was a white Frenchman who fled Saint-Domingue in the early days of General Toussaint L'Ouverture's revolution in Haiti. The elder Plessy settled in New Orleans and married Catherine Mathieu—a free Black woman—and together they had eight children (including Joseph Plessy, Homer's father).

As a young adult, Homer Plessy became a shoemaker by trade and supplemented his income as a postal clerk and insurance agent. In 1887, as Louisiana, like most of its former Confederate sister states, began drafting laws that usurped Black rights under the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, Plessy joined and soon became vice president of the "Justice, Protective, Educational, and Social Club," a group that unsuccessfully challenged the segregation of Orleans Parish public schools. Curiously, Louisiana’s public schools had become segregated after Reconstruction despite a provision in the Louisiana state constitution that prohibited the establishment of separate schools on the basis of race.

Plessy's journey into American historical infamy would begin on June 7, 1892, when he presented to the Press Street Depot in New Orleans, bought a first-class ticket to Covington, and boarded the East Louisiana Railroad’s Number 8 train. Plessy knew that the nascent segregation customs would compel the train's conductors to force him off the train and/or have him arrested. In a scene that would be replicated decades later by Rosa Parks in Montgomery, Alabama, the train conductor asked Plessy, a fair skinned Black man who could have passed for white (but was unapologetically Black), whether he was "Colored." After boldly replying "yes," the conductor demanded that Plessy move to the "Colored" car and when Plessy refused, he was dragged off the train and thrown into jail.

The next morning, Plessy was charged with violating Louisiana's "Separate Car Act" and his lawyers moved to dismiss on the grounds that the law violated the 14th Amendment's provision of equal justice regardless of race. After the motion was denied, his lawyers appealed the decision to the Louisiana Supreme Court and after considering arguments, that court upheld the lower court's decision. This set the stage for an appeal to the United States Supreme Court, one that ultimately held that Louisiana's "Separate Car Act" was constitutional because it provided "separate, but equal" accommodations to white and Black passengers alike. This decision, as referenced above, gave the individual states full authority to segregate on account of race—an authority that would remain legally intact until 1954, when the Brown vs Board of Education case overturned this ignominious precedent.

As for Plessy, after suffering defeat in the United States Supreme Court, he paid the $25 fine and spent the rest of his life quietly working as a laborer and insurance salesman until his death in 1925 in Metairie, Louisiana.

Lest we forget...

I can't remember which book, but I had read this account before. Still blows my mind.