I have never prayed for a stranger more than I prayed for Damar Hamlin, the Buffalo Bills safety who suffered cardiac arrest following a routine tackle of Cincinnati Bengals receiver Tee Higgins (below) during a highly anticipated Monday Night Football game last week.

By week's end, Hamlin, 24, was alive, alert, and publicly thanking millions of supporters worldwide who prayed to their god(s) or sent positive vibes on his behalf.

Hamlin, bottom right, was all smiles on a FaceTime call with Rapper Meek Mill after his miraculous recovery…

The end of the week—and Hamlin's improved health—also provided a backdrop into a debate that's as old as the game itself, which is whether football, a sporting spectacle often compared to the ancient gladiatoral games in Rome, is too dangerous to continue in its current form?

When pondering this question, my erudite side knows that the physics of 200 and 300 pound men slamming into each other at maximum speed will routinely yield broken limbs, torn ligaments, and brain injuries that result in gradual cognitive decline. But my primal side, the one that has the same base hunter-pugilistic instincts as my ancient forebears, cannot imagine a world without a game that I've loved since I could walk and talk in complete sentences. I am not alone in my mixed feelings; the day after Hamlin's hospitalization, the social media responses that I read were overwhelmingly in favor of supporting football—inherent dangers and all.

Part of my love for the game stems from knowing that, on a personal level, I very likely do not exist in my current form but for the game of football. How, you ask? While my real life friends and faithful readers already know this, the simple truth is that if my father, Charles Hobbs, had not earned a scholarship to play football and study political science at Florida A&M University in 1958, he never meets or eventually marries Vivian Williams—an English major who enrolled at the same prestigious HBCU in 1961.

This Miami Herald newspaper front page picture of the 1961 FAMU Rattlers includes #64, junior guard/linebacker Charles Hobbs from Miami George Washington Carver Senior High School.

Interestingly enough, my father never forced football on me like some men do, but I was around the game as soon as I could walk because back then, the U.S. Army allowed soldiers on base to play semi-professional football against other bases and regional semi-pro teams. As a Captain and Major, my old man coached the team—and played his old linebacker position for Fort Benning from 1974-76—my second and fourth years on Earth. Indeed, some of my earliest memories are of watching these large men run and slam themselves into each other over and over in the blazing hot Georgia sun—and I loved being out there with the guys!

Several years later, when I was in first grade, I begged my father to allow me to play tackle football for the Allentown Boys & Girls Club in Oxon Hill, Maryland, but he refused and encouraged me to play basketball and baseball instead because he felt that kids my age were "too small" for full contact football. That didn't stop me from asking each and every year until finally, when I was in sixth grade and living in Tallahassee, Florida, he allowed me to play for a very talented Jake Gaither Park Giants junior league team.

Two years later, prior to 8th grade, I asked dad's permission to try out for the FAMU High JV football team and, to my surprise, he gave his blessing. While I had been large for my age and more than held my own in junior league play for the Gaither Giants, I was much smaller than the 9th-12th graders that were fellow JV and varsity players for the Baby Rattlers. This reality was made crystal clear to me during the first day that we went "live" in full pads; during one tackling drill, I felt a sharp, painful pinch in my left arm and when I jumped up from the pile, that was the first time that I had ever seen the so-called “white meat" under my scraped off brown skin— a white layer that quickly turned into a bloody red mess that required immediate medical attention from the trainer. That September, during our first game against North Florida Christian School, I had to sit out a quarter because I hyperextended my knee—and was dragged off of the field by my teammate, Mike Anderson, and our coach. Lance Paul, to a mortified mother who had a look on her face that screamed “why are you playing this game” 😆. Those injuries, though, never stopped my enthusiasm—or love—for football.

A few years later, after playing a game during my junior year at Florida High School in October of 1988, I noticed on the ride home that I couldn't catch my breath; while I had suffered occasional asthma attacks since I was a small child, this inability to breathe was different—way different—that entire Saturday and on into Sunday.

That Sunday night, when my father took me to the emergency room the tests revealed that my right lung had totally collapsed! I spent the next three days in ICU and almost two full weeks recovering from an injury that my physician, Dr. Dan Davis, said could have led to cardiac arrest—and death—had it not been treated.

Now, like most men from his era, my father was not one to show much empathy—that was always my mother's forte. But one afternoon before I was released from the hospital, he popped in to visit me during the middle of the day and and asked whether I wanted to continue playing football. I remember hesitating because, at 16, I was still quite spooked by Dr. Davis's blunt "you could have had cardiac arrest" comment that made me ponder whether my life was worth a sport that I already knew that I wasn't good enough to pursue as a career? While I loved the game and my camaraderie with my teammates, I never was one of those kids who would fire off "pro football player" when adults asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, because I knew that I wanted to be a naval officer, a lawyer, and a writer—period! In fact, when I was alone in that hospital room at night I got to thinking about my future and feared that a collapsed lung would all but disqualify me from Naval ROTC, so I told dad how I felt, and his blunt reply was that ROTC was very likely out of the question due to my health, while adding that I didn't have to play ball to go to Morehouse College or Howard University because my financial reality in 1988 was not the same as his reality as a high school senior in 1958. Dad added,“ son, I knew that I had to knock n*ggas out on that football field to go to school because being the oldest of five children, there wasn’t money for all of us to get an education—but you don’t!”

Point taken!

While I didn't make my final decision during that conversation, dad's reassurances that I didn't have to play football to impress him was just the catalyst I needed to morph from active football player to avid football spectator!

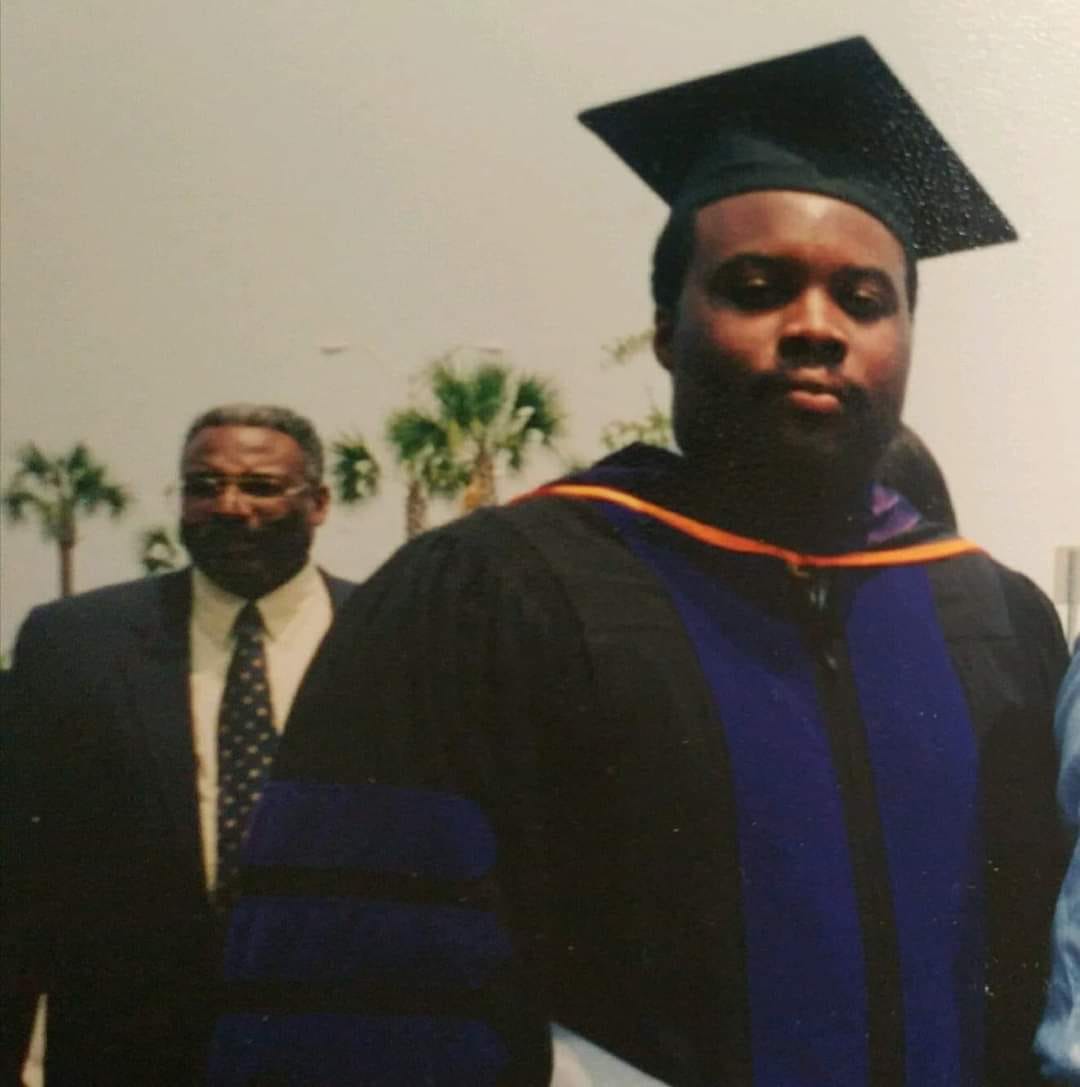

A proud Charles Sr watching his son and namesake graduate from the University of Florida Levin College of Law a little over a year before he died of prostate cancer.

Such is why I can't, in good conscience, advocate a position that would remove the ability for other young men (and increasingly, women) to play football, a sport that, for some, still provides educational opportunities or lucre that exceeds most other professions.

Yes, the risks from football remain legion—just as it was during the turn of the 20th Century when the sport was almost banned by Congress due to myriad injuries and deaths. In fact, The Chicago Tribune reported that, “in 1904 alone, there were 18 football deaths and 159 serious injuries, mostly among prep school players. Obituaries of young pigskin players ran on a nearly weekly basis during the football season. The carnage appalled America…”

So yes, Damar Hamlin's near-death experience was frightening last week, but there's a part of me that respects his right to choose to play the game—or not—as I did when I chose to walk away prior to spring practice in 1989.

And yes, I respect the rights of those who despise football due to its violence to choose to neither watch or support the game. I get it, I really do, but once more, the very essence of freedom is the ability for Americans to choose what to do with their bodies—even if that means putting on pads and risking catastrophic injuries or death during 60 minutes of play on any given Thursday-Sunday.

Now, I still maintain all sorts of grievances about football, from racial dynamics to health dilemmas as discussed herein, but still, flaws and all, I am drawn to viewing the sport like a moth to a flame…

Great piece. My oldest regrets that he didn't play high school football, but I think it was a good decision since he broke his wrist and clavicle playing middle school football.

Great piece, Hobbs!