The ghosts of Tuskegee and Black reticence to take the Covid-19 vaccine

The NY Times this morning reports a Kaiser Family Foundation study that finds that Republicans, rurals, and Black Americans are the least likely to be inoculated by one of the two Covid-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer/BioNtech and Moderna Pharmaceuticals–vaccines that were authorized for distribution last week by the FDA.

With the U.S. suffering approximately 2,400 deaths a day–the highest totals this year–one would think that an American public that is weary from mask wearing, social distancing and other life saving but quality of life changing measures, would be lining up en masse for the treatment. But the Kaiser official study, and my “Hobbservation” unofficial study–which is anecdotal evidence culled from my social media pages–leaves me unsurprised that the next major step for epidemiologists, pharmacists, and medical providers is convincing the skeptics of the safety and efficacy of these vaccines.

Where Blacks are concerned, this task shan’t be easy as the deeply held fears of substandard medical care from slavery to Jim Crow–including the infamous Tuskegee Syphillis study, will not be easily assuaged.

To be clear, Black fears of medical science are not irrational; when I was a 30-year old lawyer, I walked into an apartment at a housing project on a sweltering July afternoon to discuss what would become one of my first major civil case settlements. The apartment lacked air conditioning, so within the first minutes of my entry, my dress shirt was stuck to my back and drenched in sweat.

It was clear that the owner of the apartment, a young Black woman, was embarrassed by its condition. First, there was the distinct smell of mold, not to mention the vermin and pests that were so bold that while I sat and consulted about the case, one that involved the wrongful death of her child due to an adverse reaction to a prescription drug, as I leaned my head against the wall, a rather large cockroach ran clear across my head until I was able to flick it off. The woman apologized profusely to which I told her that all was well and to continue telling me about the facts of her child’s case.

Her deceased child had received what I believed to be substandard medical care due, perhaps, to the facts that Medicaid only paid for so much, and because when poor folks present to emergency rooms, suffice it to say that at times, medical mistakes are made that likely would not occur if the patient had the best health insurance. Nevertheless, the woman’s child was dead due to a medical reaction that one top expert witnesses would later testify could have been avoided with due care.

As the young mother signed the contract allowing my firm to represent her, I sensed that what made the difference in her selecting me over more established white firms that had reached out to her was that I was willing to come to visit her at her residence as she, too, was in very poor health. And while I left the apartment that day reminded to be grateful for all of the material blessings that I had, the visit reinforced in my mind what I already knew, which is that poverty and race greatly impact the standard of medical care.

As students of history well know, enslaved Africans and sharecroppers lived in dolorific conditions–shacks that barely prevented the elements from taking their toll on their poorly dressed bodies. They often subsisted off of scraps from the slave master or company store owner’s tables, thus beginning the pervasive hypertension that many Blacks–including I–suffer from daily, thus leaving us exposed to the worst results of Covid-19 to this very day.

Which leads me to the main point, the Tuskegee syphilis experiments. The study originally involved 600 black men–399 with syphilis, 201 without it, with the subjects told that the researchers were studying “bad blood.” Even when penicillin was found to be a suitable treatment for the disease, the participants were never given the treatment but in exchange for their suffering and cooperation, they were given free medical exams, food, and burial insurance. This macabre study lasted from 1932 to 1972–the year that I was born–and probably would have continued unabated but for an Associated Press news article that blew the story wide open.

While a class action lawsuit ultimately settled the Tuskegee case against the government for a paltry $10 million, paltry due to the sheer numbers of families impacted by this sham, the government also agreed to provide medical and burial insurance for the spouses and children of the participants. The last study participant died in 2004, the last spouse died in 2009, and today, 11 children are still alive and receiving benefits.

Cognizant of this history, trust me when I state that I fully understand why many Blacks are deeply skeptical about the Covid-19 vaccine. With reasons ranging from Tuskegee to these Covid vaccines being developed in record time, there is a feeling among some Brothers and Sisters that this could be a disaster waiting to happen to our Black bodies.

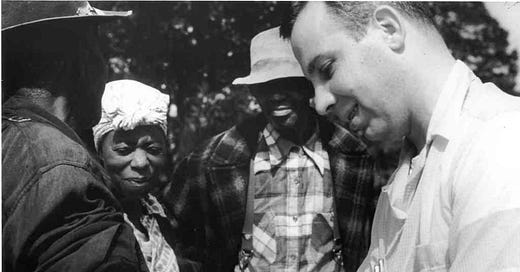

I would counter that there are differences, stark differences, from the Tuskegee era to now. First, there is no covert governmental activity that targets Black people, specifically, with regards to Covid-19. Second, and perhaps the most important difference, is that the lead researcher for this vaccine is Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, pictured below, a leading immunology expert at the National Institutes of Health. In addition to her multiple degrees in biology from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and the University of Maryland, Dr. Corbett also holds a degree in sociology and is fully aware of the many instances within which medical science has failed the public writ large, including the Tuskegee experiments.

Another difference is that in the 48 years since the Tuskegee experiments were exposed, the number of Black physicians, pharmacists, nurses, epidemiologists, and immunologists have increased exponentially and many of these professionals are taking to mainstream media and social media to encourage Black people to discuss these vaccines with their providers and to strongly consider getting vaccinated. On my Hobbservation Point Roundtables, HBCU alums Dr. Rodney Alan (Morehouse), Dr. Hernando Carter (Morehouse), Dr. Millicent Ford (FAMU), Dr. Ericka Goodwin (Spelman), Dr. Sonya Marks (Spelman), Dr. Bill Norris (Morehouse), and Dr. Michael Smith (FAMU) each has either gone on air or provided off air context about Covid-19 and the need for Black people to be fully informed about this deadly disease and the proper treatments.

As one with several co-morbidities, I definitely plan to discuss the vaccine with my own doctor, Dr. Remelda Saunders-Jones, a FAMU and Meharry Medical College graduate who holds both an MD and a PharmD. If Doc gives the green light, I most certainly intend to take the vaccine and continue mask wearing and social distancing. To that end, I strongly suggest that Brothers and Sisters discuss the vaccines with your providers, too, to help distinguish science fact from science fiction in the days ahead.

Hobbservation Point is a news/editorial site that is free from corporate censorship. Please support our aims by donating today!

Basic Service - $10Gold Service - $20Platinum Service - $30Onyx Service - $50Your Email Address: