Today would have been George Stinney's 92nd birthday but due to false allegations of murder, he was arrested, tried, convicted, and executed by the State of South Carolina four months shy of his 15th birthday in 1944.

When I entered law school at the University of Florida in the mid-90s, I was a political moderate who leaned rather conservative on crime and punishment, which included my full support of the death penalty. By the time I exited school, I would be an ardent death penalty opponent, primarily due to the teachings of my mentor, UF Law Professor Kenneth Nunn, who asked me to come to his office one morning after I half-jokingly remarked that the State of Florida should enact an “electric couch” to clear out its backlog of Death Row defendants.

As mentors often do for their bright, opinionated, but woefully misinformed mentees, Nunn handed me several articles and books that contained statistics that immediately shifted my perspective, with the basic underpinning being that in the 20th Century, the death penalty was overwhelmingly skewed against Black men for the alleged crimes of murder and rape of white people—while whites who murdered or raped Blacks avoided the death chamber (in the event they were convicted at all).

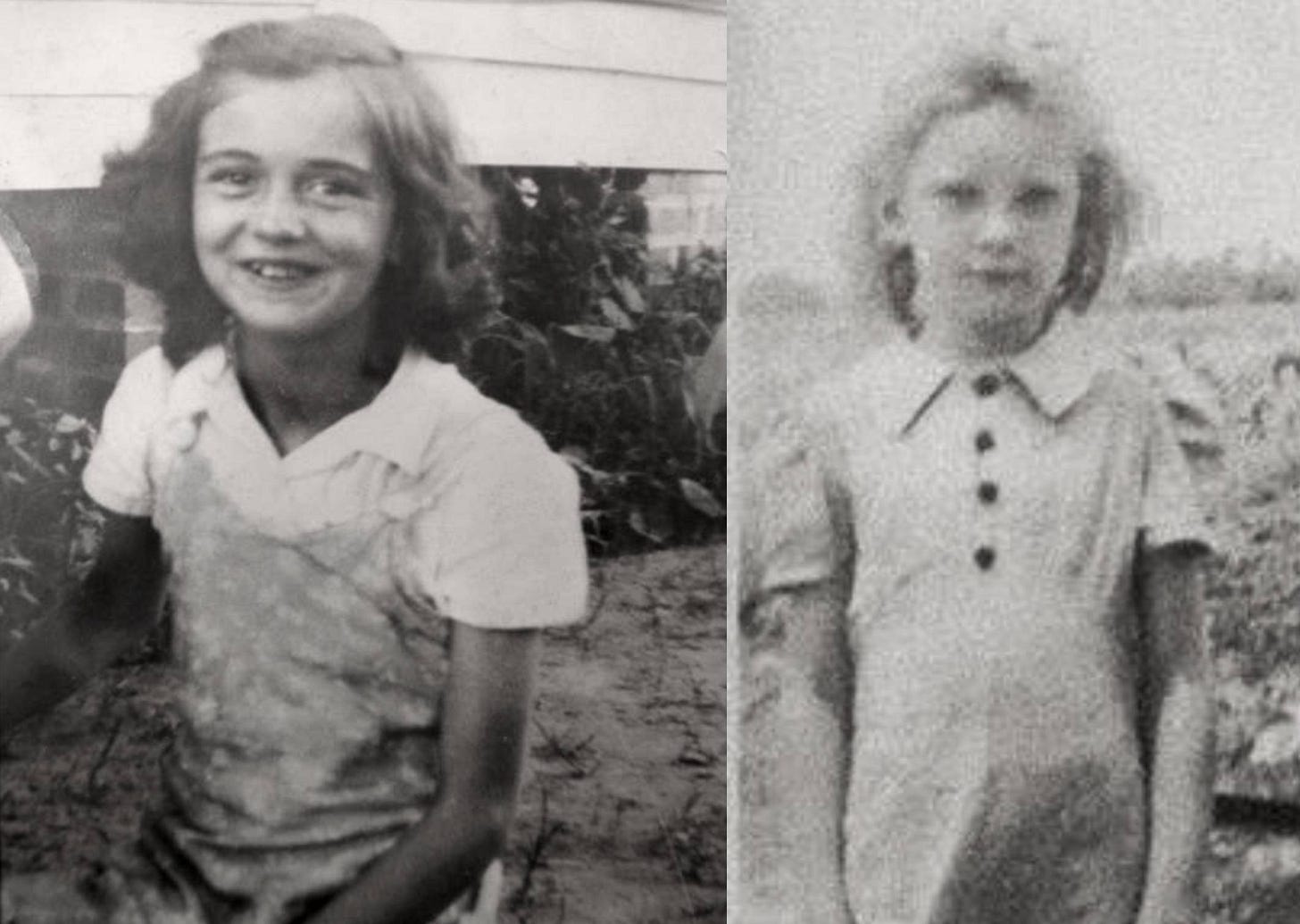

It was during these class and office sessions with Prof. Nunn, and my own assiduous reading on the racial aspects of state sponsored capital punishment, that I learned of Stinney, 14, who was arrested on March 23, 1944 after the lifeless bodies of two white girls, Betty June Binnicker and Martha Thames, ages 11 and 8, were found in a muddy ditch near Alcolu, South Carolina.

Not long after their discovery, Stinney was arrested by local law enforcement and interrogated by police officers for hours without the advice or assistance of legal counsel or the presence of his parents, two factors that are routine in our modern era with regards to juvenile suspects.

Officers later contended that the diminutive Stinney, who stood at 5’1” and weighed only 90 pounds, had confessed to wanting to have sex with the elder girl, Betty, and that to facilitate the same, he claimed to have killed the younger Martha first—and then Betty—by blunt trauma to the head. Officers further claimed that Stinney said that the girls had “fought back,” however, no pictures were taken of Stinney’s body that may have corroborated signs of a struggle. Even worse, no murder weapon was found and forensic testing determined that neither girl showed signs of sexual abuse.

The townspeople, eager for Jim Crow era vengeance, began clamoring for a lynching, but such was averted by local officials who decided to move Stinney to Charleston for safe keeping. The day of his arrest, Stinney’s father was fired from his job in a lumber yard and fearing for their own safety, fled the area with the remainder of his family where they eventually settled in Tennessee.

On April 24th, barely one month after the murders, Stinney was brought to trial. Stinney’s court appointed lawyer, Charles Plowden, offered little defense and refused to cross-examine witnesses. The trial proceedings, which began with jury selection at 10:00 a.m., ended by 5:00 p.m., with the all-white male jury deliberating for a paltry 10 minutes before convicting Stinney, after which the judge sentenced him to die by electrocution.

Lorraine Binnicker Bailey, the victims oldest sister, later recounted that “Everybody knew that he done it, even before they had the trial they knew that he done it. But, I don't think that they had too much of a trial.”

On June 16, 1944, Stinney was escorted to the electric chair only weeks removed from a hasty investigation, a sham jury trial, and a summary sentence of death, a series of events that can only be described as a state sponsored lynching.

Because of Stinney's tiny physical stature, prison officials found great difficulty attaching the electrodes to his body; the mask that administers electrical currents to the head was clearly too large to fit him. To facilitate matters, the executioner placed a large Bible on the seat to prop Stinney up to receive his fate. When the switch was flipped to shoot the electrical currents through Stinney’s body, eyewitnesses recounted that he jerked so violently that that the mask was dislodged—exposing his face to the 40 or so witnesses, including the Binnicker and Thames families, who watched the macabre spectacle in real time. A few moments later, Stinney was pronounced dead.

In 2014, 70 years after his execution, Stinney's conviction was vacated by Court Order due to concerns that his confession had been coerced and that his trial had been a miscarriage of justice.

Lest we forget...

Thank you for subscribing to the Hobbservation Point Newsletter—have a great Thursday.

Such a sad and evil story of racism and injustice. The TV movie Carolina Skeletons was based on this.

Great writing. Heart breaking. Thank you for honoring him by sharing his story and your change of heart re: the death penalty. When I clerked in the 4th Cir, I was the unofficial, "Death Penalty Law Clerk," in chambers, seeking to desperately determine if the appeals submitted provided ANY grounds for relief. In my one year of serving, I found one--a miscarriage of justice for a Black man in NC. Two years after my term ended, the 4th Cir. heard the case, en banc, and vacated his death sentence, remanding the case back to the lower court.