Throwback Thursday: The first Kappa Hazing case ended 15 years ago this week

Ol' Hobbs's Thursday Thoughts

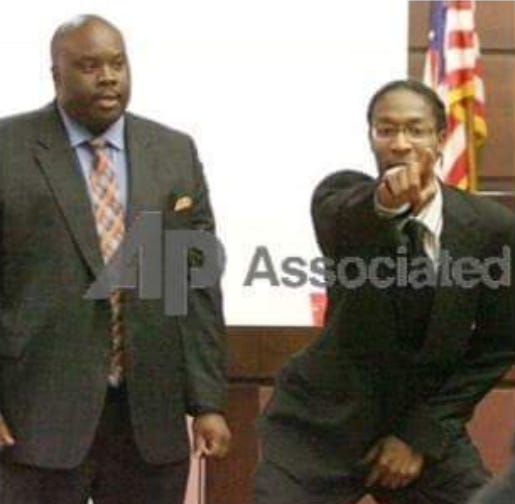

The Facebook App's memory section reminded this morning that the picture of me below with Attorney Richard Alan was published fifteen years ago today during the final moments of what had become known as the "Kappa Hazing case," one covered gavel to gavel on CourtTV, CNN, and by the Associated Press.

What most of the press corps did not know was that Alan and I had grown up together in Tallahassee, been roommates at Morehouse College, and were bonded in a way that allowed our ease in attacking the criminal charges against five young members of the Alpha Xi Chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Florida A&M University with the same passion that we displayed when debating all comers during our days at Morehouse.

Alan represented Jason Harris, while I represented Brian Bowman, Cory Gray, Marcus Hughes, and Michael Morton, each a brilliant student leader on FAMU's campus. The allegations held that the quintet had beaten an interested prospect named Marcus Jones and in the process, bruised his buttocks and perforated his ear drum.

What initially made the case intriguing was that prior to the Florida Legislature’s passing of the Chad Meredith HazingAct in 2005, most states charged hazing as a misdemeanor and in cases in which more serious injuries occurred, either aggravated battery or manslaughter charges were levied. At that time (and in those instances), the accused were allowed to use the common law defense of "consent" and argue that the victim willingly submitted to the acts, thus, negating criminal culpability.

The Meredith Act, however, removed victim consent from the equation and by so doing, raised the stakes for student organization members arrested under its tenets.

The "Kappa Five," as the media would call them, drew international media attention because their case would be the first in which hazing, per se, could lead to five years imprisonment.

In the run up to the trial, Attorney Alan and I were deluged with requests for comments from the media, and while I had served as co-counsel in the spectacle that was former Florida State University quarterback Adrian McPherson's gambling case in 2003, that case paled in comparison to the number of media requests that court administrators noted were being issued to sit and watch what would become a nearly three week grind towards justice.

During the first trial in September of 2006, a Leon County jury was unable to reach a verdict, in large measure because the trial judge, the Honorable Kathleen Dekker, failed to define the meaning of “serious bodily injury” with respect to Marcus Jones. During the defense case-in-chief, we were able to elicit expert testimony that suggested that Jones's injuries were far less severe than his personal doctors had alleged—while also discrediting his testimony that while blindfolded and facing forward to be struck with a cane, that he actually could see who, in fact, struck him in a room filled with dozens of fraternity brothers.

After remaining deadlocked for over a day's worth of deliberating, Judge Dekker declared a mistrial. The lead prosecutor, then Assistant State Attorney (now Circuit Judge) Frank Allman, immediately declared his intention to try the case again in December.

During the retrial, after another near two week battle, a separate jury was similarly hung as to the guilt of young Bowman, Gray and Hughes, but later returned verdicts of guilty against Morton, who was the chapter polemarch (president), and Harris.

A few weeks later, one of the more frustrating days in my legal career ensued during the sentencing hearing for Morton and Harris, where a packed courtroom—literally hundreds of onlookers spilling out into the hallways—was unusually tense as FAMU students, professors and staff, and even prosecutors waited to learn their fate. During the three hour hearing, the defense called a number of prominent witnesses, including former FAMU president Dr. Fred Gainous, who established the many good deeds and sterling academic records of both Morton and Harris.

Based upon my experiences with Judge Dekker, I sensed that the pair would have to serve some jail time; they had been incarcerated for nearly six weeks following the jury’s verdict, so I figured that they would receive between 90 and 180 days followed by probation and community service. Morton, in fact, was soon to be a father and during the proceedings, read a gut wrenching nine page missive to Dekker about the impact that growing up without a father had on his life, and why he wanted to be a great father from the very first moment of his child’s birth.

Judge Dekker seemed totally impervious to the request, and her pronouncement that the pair would serve two (2) years in prison reduced much of the courtroom into shrieks of anguish and tears. Even worse, a few weeks later, Dekker refused a defense request for the sentences to be stayed until such time as the appeals court could review the trial case—an accommodation that usually is routine when the defendants are charged with relatively minor crimes (Hazing is a 3rd degree felony—the lowest form—in Florida). Neither Morton nor Harris had ever been charged with any criminal infraction in their short lives, but Dekker ordered them to begin serving her two year sentence in the Florida Department of Corrections.

Judge Dekker’s refusal to grant an appeals bond stung even worse late the following year when the First District Court of Appeal vacated the pair’s convictions based, in part, upon her refusal to properly define “serious bodily injury” in her jury instructions as the defense had requested. What hurt is that the tossed out convictions came after the two Brothers had already served the majority of their sentences 😠.

Now, a vacated sentence meant that the State could have tried them again albeit with the requested jury instruction on injury, but in the approximately 20-months since their incarceration, Bowman, Gray, and Hughes had plead no contest to misdemeanor hazing and been sentenced to community service; Morton and Harris were later allowed to plea to time served. If there is any silver lining at all, it is that each of these five young men would go on to graduate and achieve greatly in corporate America, education, engineering, pharmacy, and as husbands, fathers, and civic leaders.

Looking back, what was particularly difficult for me during these trials was a very personal element in that I, too, was a member of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity. During a break in trial, one reporter, upon learning this fact, jokingly asked whether I had been involved in beating Jones, which he soon nervously apologized for when I asked whether he was that idiotic to ask me such an asinine question.

But for those unaware, Black Greek Letter Organizations differ from many of their non-Black counterparts in that members often remain devoted members for life. Through the years, the alumni of these organizations have read like a page of American history, including such luminaries as Attorney Johnnie L. Cochran (Kappa), Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., (Alpha Phi Alpha), Dr. Carter G. Woodson (Omega Psi Phi), Congressman John Lewis (Phi Beta Sigma), Rosa Parks (Alpha Kappa Alpha), actress Lena Horne (Delta Sigma Theta), writer Zora Neale Hurston (Zeta Phi Beta), actress Hattie McDaniel (Sigma Gamma Rho), and U.S. Representative Bobby Rush (Iota Phi Theta). Members of these organizations have served as the backbone of what philosopher Dr. W.E.B. Dubois termed the “talented tenth,” a group of educated Blacks who would lead the race to greater economic prosperity. That Dubois, himself, was an Alpha is further indicative of how deeply ingrained the Black Greek system is within the Black middle and upper classes.

If one was to poll most active members of these organizations, the general consensus among alumni members is that hazing is morally and legally wrong. What often leads to confusion among younger prospective members is how some older members regale in stories of having been hazed in their youth; younger prospects often mistakenly believe that acceptance is predicated upon submission to hazing. For that reason, what once were ritual acts promulgated in the open on campuses have morphed into underground wanton and reckless beatings, so much so that even the most ardent “old school” hazing proponents realize that any symbolism is often lost in the rush to simply beat the hell out of prospective members.

Second, quite a few members of these organizations are initiated into alumni chapters—not as undergraduates. Most (surely not all) alumni initiates do not participate in the physical or mental trials that are more common, albeit illegal, within the undergraduate process. This has often led to one of the more inane arguments among Black Greeks, the notion of whether one is “real”—meaning you got hazed—or “paper”—meaning you paid your dues, learned the history, and was declared a brother or sister in short order. The desire to be “real” is so real that there are even times in which grown men and women—some in their 30’s and 40’s, have been known to submit to physical hazing for the purpose of acceptance, a fact that leads me to conclude that hazing, albeit illegal, will never die so long as their are willing suppliers—and eager prospects that demand a process that in its most extreme forms, has left people deformed…or dead…

Thank you for subscribing to the Hobbservation Point Newsletter. Have a great Thursday!

Very educational.

I remember this case.